Showing posts with label 18th Dynasty. Show all posts

Showing posts with label 18th Dynasty. Show all posts

Amenhotep III. 18th Dynasty

(Don't forget to sign up for the FREE Egyptology course from Ancient Egypt History)

(18th Dynasty, part XIII)

Chronicles of the Pharaohs

If you want to learn more about the Pharaohs of ancient Egypt, you will love the book Chronicle of the Pharaohs: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt (The Chronicles Series) .

.

This book tells you the complete story of ancient Egypt through its pharaohs' lives. You will not only learn about the famous pharaohs, but you will also meet infamous pharaohs, maybe for the first time.

Purchase your copy from Amazon and write a review about it here for other visitors, please.

(18th Dynasty, part XIII)

Amenhotep III's long reign of almost 40 years was one of the most prosperous and stable in Egyptian history. His great-grandfather, Tuthmosis III, had laid the foundations of the Egyptian empire by his campaigns into Syria, Nubia and Libya. Hardly any military activity was called for under Amenhotep III, and such little as there was, in Nubia, was directed by his son and viceroy of Kush, Merymose.

Amenhotep III was the son of Tuthmosis IV by one of his chief wives, Queen Mutemwiya. It is possible [though now doubted by some) that she was the daughter of the Mitannian king, Artatama, sent to the Egyptian court as part of a diplomatic arrangement to cement the alliance between the strong militarist state of Mitanni in Syria and

Egypt. The king's royal birth is depicted in a series of reliefs in a room on the east side of the temple of Luxor which Amenhotep III built for Amon. The creator god, the ramheaded Khnum of Elephantine, is seen fashioning the young king and his ka (spirit double) on a potter's wheel, watched by the goddess Isis. The god Amun is then led to his meeting with the queen by ibis-headed Thoth, god of wisdom. Subsequently, Amun is shown standing in the presence of the goddesses Hathor and Mut and nursing the child created by Khnum.

Amenhotep III was the son of Tuthmosis IV by one of his chief wives, Queen Mutemwiya. It is possible [though now doubted by some) that she was the daughter of the Mitannian king, Artatama, sent to the Egyptian court as part of a diplomatic arrangement to cement the alliance between the strong militarist state of Mitanni in Syria and

Egypt. The king's royal birth is depicted in a series of reliefs in a room on the east side of the temple of Luxor which Amenhotep III built for Amon. The creator god, the ramheaded Khnum of Elephantine, is seen fashioning the young king and his ka (spirit double) on a potter's wheel, watched by the goddess Isis. The god Amun is then led to his meeting with the queen by ibis-headed Thoth, god of wisdom. Subsequently, Amun is shown standing in the presence of the goddesses Hathor and Mut and nursing the child created by Khnum.

The early years of Amenhotep III

Amenhotep III's reign falls essentially into two unequal parts. The first decade reflected a young and vigorous king, promoting the sportsman image laid down by his predecessors and with some minor military activity. In Year 5 there was an expedition to Nubia, recorded on rock inscriptions near Aswan and at Konosso in Nubia. Although couched in the usual laudatory manner, the event recorded seems to have been rather low key. An undated stele from Semna (now in the British Museum) also records a Nubian campaign, but whether it is the same one or a later one is uncertain. A rebellion at Ibhet is reported as having been heavily crushed by the viceroy of Nubia, "King's Son of Kush", Merymose. Although the king, 'mighty bull, strong in might, the fierce-eyed lion' is noted as having made great slaughter within the space of a single hour, he was probably not present; nevertheless, 150 Nubian men, 250 women, 175 children, 110 archers, and 55 servan a total of 740 - were said to have been captured, to which was added the 312 right hands of the slain.

Amenhotep III's reign falls essentially into two unequal parts. The first decade reflected a young and vigorous king, promoting the sportsman image laid down by his predecessors and with some minor military activity. In Year 5 there was an expedition to Nubia, recorded on rock inscriptions near Aswan and at Konosso in Nubia. Although couched in the usual laudatory manner, the event recorded seems to have been rather low key. An undated stele from Semna (now in the British Museum) also records a Nubian campaign, but whether it is the same one or a later one is uncertain. A rebellion at Ibhet is reported as having been heavily crushed by the viceroy of Nubia, "King's Son of Kush", Merymose. Although the king, 'mighty bull, strong in might, the fierce-eyed lion' is noted as having made great slaughter within the space of a single hour, he was probably not present; nevertheless, 150 Nubian men, 250 women, 175 children, 110 archers, and 55 servan a total of 740 - were said to have been captured, to which was added the 312 right hands of the slain.

The opulent years of Amenhotep III

The last 25 years of Amenhotep III's reign seem to have been a period of great building works and luxury at court and in the arts. The laudatory epithets that accompany the king's name are more grandiose metaphen than records of fact: he took the Horus name 'Great of Strength who Smites the Asiatics', when there is little evidence of such a campaign, similarly, 'Plunderer of Shinar' and 'Crusher of Naharin' seem singularly inappropriate, particularly the latter since one of his wives, Gilukhepa, was a princess of Naharin.

The last 25 years of Amenhotep III's reign seem to have been a period of great building works and luxury at court and in the arts. The laudatory epithets that accompany the king's name are more grandiose metaphen than records of fact: he took the Horus name 'Great of Strength who Smites the Asiatics', when there is little evidence of such a campaign, similarly, 'Plunderer of Shinar' and 'Crusher of Naharin' seem singularly inappropriate, particularly the latter since one of his wives, Gilukhepa, was a princess of Naharin.

The wealth of Egypt at this period came not from the spoils of conquest, as it had under Tuthmosis III, but from international trade and an abundant supply of gold (from mines in the Wadi Hammamat and from panning gold dust far south into the land of Kush). It was this great wealth and booming economy that led to such an outpouring of artistic talent in all aspects of the arts.

Since the houses or palaces of the living were regarded as ephemeral, we unfortunately have little evidence of the magnificence of a palace such as Amenhotep's Malkata palace. Fragments of the building, however, indicate that the walls were once plastered and painted with lively scenes from nature. Many of the temples he built have been destroyed too. At Karnak he embellished the already large temple to Amun and at Luxor he built a new one to the same god, of which the still standing colonnaded court is a masterpiece of elegance and design. Particular credit is owed to his master architect: Amenhotep son of Hapu.

On the west bank, his mortuary temple was destroyed in the next (19th) dynasty when it, like many of its predecessors, was used as a quarry. All that now remains of this temple are the two imposing statues of the king known as the Colossi of Memnon. (This is in fact a complete misnomer, arising from the classical recognition of the statues as the Ethiopian prince, Memnon, who fought at Troy.) Of the two, the southern statue is the best preserved. Standing beside the king's legs, dwarfed by his stature, are the two important women in his life: his mother Mutemwiya and his wife, Queen Tiy. A quarter of a mile behind the Colossi stands a great repaired stele that was once in the sanctuary and around are fragments of sculptures, the best of which, lying in a pit and found in recent years, is a crocodile-tailed sphinx.

Since the houses or palaces of the living were regarded as ephemeral, we unfortunately have little evidence of the magnificence of a palace such as Amenhotep's Malkata palace. Fragments of the building, however, indicate that the walls were once plastered and painted with lively scenes from nature. Many of the temples he built have been destroyed too. At Karnak he embellished the already large temple to Amun and at Luxor he built a new one to the same god, of which the still standing colonnaded court is a masterpiece of elegance and design. Particular credit is owed to his master architect: Amenhotep son of Hapu.

On the west bank, his mortuary temple was destroyed in the next (19th) dynasty when it, like many of its predecessors, was used as a quarry. All that now remains of this temple are the two imposing statues of the king known as the Colossi of Memnon. (This is in fact a complete misnomer, arising from the classical recognition of the statues as the Ethiopian prince, Memnon, who fought at Troy.) Of the two, the southern statue is the best preserved. Standing beside the king's legs, dwarfed by his stature, are the two important women in his life: his mother Mutemwiya and his wife, Queen Tiy. A quarter of a mile behind the Colossi stands a great repaired stele that was once in the sanctuary and around are fragments of sculptures, the best of which, lying in a pit and found in recent years, is a crocodile-tailed sphinx.

A peak of artistic achievement of Amenhotep III

Some magnificent statuary dates from the reign of Amenhotep III such as the two outstanding couchant rose granite lions originally set before the temple at Soleb in Nubia (but subsequently removed to the temple at Gebel Barlzal further south in the Sudan). There is also a proliferation of private statues, particularly of the architect Amenhotep son of Hapu, but also of many other nobles and dignitaries.

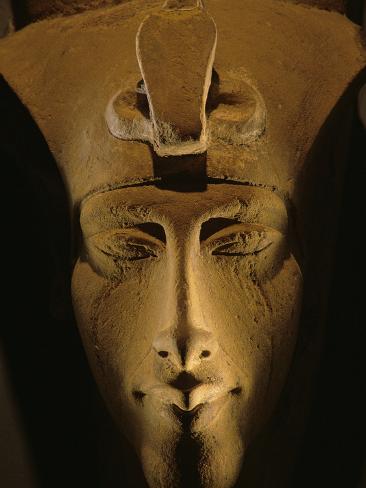

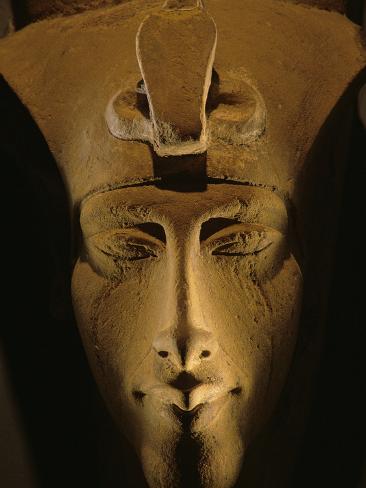

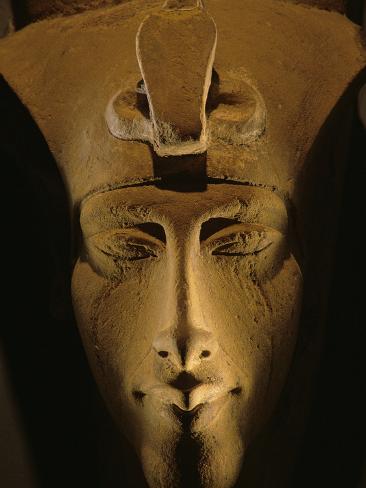

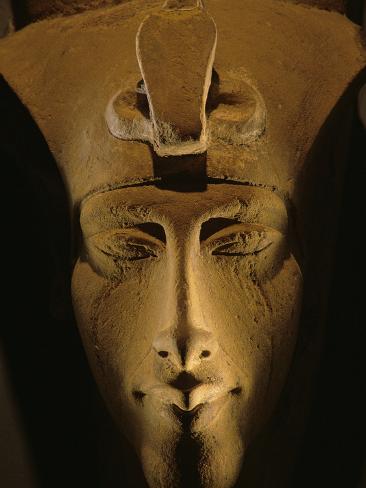

It is in the great series of royal portraits, however, that the sculptor's art is truly seen. Largest of them all (after the Colossi of Memnon) is the huge limestone statue of the king and queen with three small standing princesses from Medinet Habu. There are many other representations of the king, all of which project the contemplative, almost ethereal, aspect of the king's features. Magnificently worked black granite seated statues of Amenhotep wearing the nemes headdress have come from excavations behind the Colossi of Memnon (by Belzoni) and from Tanis in the Delta. A number of statues of the king were reworked by later rulers, often by simply adding their cartouches, or occasionally altering the features or aspects of the body, as with the huge red granite head hitherto identified as being Tuthmosis III from Karnak (also found by Belzoni) and reworked by Ramesses II [now in the British Museum). Several portraits in statues, reliefs and wall paintings show the king wearing the helmet-like khepresh, the so-called Blue or War Crown.

One of the most incredible finds of statuary in recent years was made in the courtyard of the Amenhotep III colonnade of the Luxor temple in 1989. It included a superb 6-ft (1.83-m) high pink quartzite statue of the king standing on a sledge and wearing the Double Crown. The only damage the statue had sustained was under Akhenaten when, very carefully, the hated name of Amon was removed from the cartouch when it appeared as part of the king's name. The inscriptions on the statue and its iconography suggest that it is a work from late in the despite the idealized youthful features of the king. It may possibly have been a cult statue.

Some magnificent statuary dates from the reign of Amenhotep III such as the two outstanding couchant rose granite lions originally set before the temple at Soleb in Nubia (but subsequently removed to the temple at Gebel Barlzal further south in the Sudan). There is also a proliferation of private statues, particularly of the architect Amenhotep son of Hapu, but also of many other nobles and dignitaries.

It is in the great series of royal portraits, however, that the sculptor's art is truly seen. Largest of them all (after the Colossi of Memnon) is the huge limestone statue of the king and queen with three small standing princesses from Medinet Habu. There are many other representations of the king, all of which project the contemplative, almost ethereal, aspect of the king's features. Magnificently worked black granite seated statues of Amenhotep wearing the nemes headdress have come from excavations behind the Colossi of Memnon (by Belzoni) and from Tanis in the Delta. A number of statues of the king were reworked by later rulers, often by simply adding their cartouches, or occasionally altering the features or aspects of the body, as with the huge red granite head hitherto identified as being Tuthmosis III from Karnak (also found by Belzoni) and reworked by Ramesses II [now in the British Museum). Several portraits in statues, reliefs and wall paintings show the king wearing the helmet-like khepresh, the so-called Blue or War Crown.

One of the most incredible finds of statuary in recent years was made in the courtyard of the Amenhotep III colonnade of the Luxor temple in 1989. It included a superb 6-ft (1.83-m) high pink quartzite statue of the king standing on a sledge and wearing the Double Crown. The only damage the statue had sustained was under Akhenaten when, very carefully, the hated name of Amon was removed from the cartouch when it appeared as part of the king's name. The inscriptions on the statue and its iconography suggest that it is a work from late in the despite the idealized youthful features of the king. It may possibly have been a cult statue.

The two most widely known portraits of Queen Tiy are the small ebony head in Berlin which, in the past, caused many authorities to suggest that she came from south of Aswan, and the petite-faced and crowned head found by Petrie at the temple of Serabit el-Khadim in Sinai which is identified as the queen by her cartouch on the front of her crown. Other fine reliefs of her come from the tombs of some of the courtiers in her service such as Userhet (TT 47) and Kheruef (TT 192).

Death and burial of Amenhotep III

Inscribed clay dockets from the Malkata palace carry dates into at least Year 38 of Amenhotep's reign, implying that he may have died in his 39th regnal year when he would have been about 45 years old.

Inscribed clay dockets from the Malkata palace carry dates into at least Year 38 of Amenhotep's reign, implying that he may have died in his 39th regnal year when he would have been about 45 years old.

His robbed tomb was rediscovered by the French expedition in 1799 in the western Valley of the Kings (KV 22). Amongst the debris, they found a large number of ushabtis of the king, some complete but mostly broken, made of black and red granite, alabaster and cedar wood. Some were considerably larger than normal. Excavations and clearance by Howard Carter in 1915 revealed foundation deposits of Tuthmosis IV, showing that the tomb had been originally intended for that king. Despite this, the tomb was eventually used for Amenhotep III, and also for Queen Tiy to judge from the fragments found of several different ushabtis of the queen.

Queen Tiy survived her husband by several years - possibly by as many as 12, since she is shown with her youngest daughter, Beket Aten, in a relief in one of the Amarna tombs that is dated between Years 9 and 12 of her son's reign. (Beket-Aten is shown as a very young child and must have been born shortly before Amenhotep died, or even posthumously.) We know from polite enquiries about Tiy's health in the Amarna Letters (p. 126) that she lived for a while at Akhetaten (modern el-Amarna), the new capital of her son Akhenaten. It has been suggested that there was a period of co-regency between the old king and his successor, but the argument is not proved either way. An interesting painted sandstone stele found in a private household shrine at el-Amarna shows an elderly, rather obese Amenhotep III, seated with Queen Tiy. Whether he actually lived for a time in this city is a matter of conjecture; Tiy certainly did and may well have died there, to be taken back to Thebes for burial.

Amenhotep III's mummy was probably one of those found by Loret in 1898 in the tomb of Amenhotep II (KV 35), although recently it has been suggested that this body was wrongly identified by the ancient priests

when it was transferred to the new tomb. On biological grounds, professors Ed Wente and John Harris have proposed it to be the body of Akhenaten, or possibly Ay. A previously unidentified female mummy (the Elder Woman) from the same cache has been tentatively identified as Queen Tiy, based on the examination of her hair and a lock of hair in a small coffin from the tomb of Tutankhamun inscriptionally identified as Tiy's.

Queen Tiy survived her husband by several years - possibly by as many as 12, since she is shown with her youngest daughter, Beket Aten, in a relief in one of the Amarna tombs that is dated between Years 9 and 12 of her son's reign. (Beket-Aten is shown as a very young child and must have been born shortly before Amenhotep died, or even posthumously.) We know from polite enquiries about Tiy's health in the Amarna Letters (p. 126) that she lived for a while at Akhetaten (modern el-Amarna), the new capital of her son Akhenaten. It has been suggested that there was a period of co-regency between the old king and his successor, but the argument is not proved either way. An interesting painted sandstone stele found in a private household shrine at el-Amarna shows an elderly, rather obese Amenhotep III, seated with Queen Tiy. Whether he actually lived for a time in this city is a matter of conjecture; Tiy certainly did and may well have died there, to be taken back to Thebes for burial.

Amenhotep III's mummy was probably one of those found by Loret in 1898 in the tomb of Amenhotep II (KV 35), although recently it has been suggested that this body was wrongly identified by the ancient priests

when it was transferred to the new tomb. On biological grounds, professors Ed Wente and John Harris have proposed it to be the body of Akhenaten, or possibly Ay. A previously unidentified female mummy (the Elder Woman) from the same cache has been tentatively identified as Queen Tiy, based on the examination of her hair and a lock of hair in a small coffin from the tomb of Tutankhamun inscriptionally identified as Tiy's.

Amenhotep III Names and Burial

Birth name: Amen-hotep (heqa-waset) (Amun is Pleased, Ruler of Thebes)

Throne name: Nub-maat-re (Lord of Tuth is Ra)

Burial: Tomb KV 22, Valley of the Kings, Thebes

If you want to learn more about the Pharaohs of ancient Egypt, you will love the book Chronicle of the Pharaohs: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt (The Chronicles Series)

This book tells you the complete story of ancient Egypt through its pharaohs' lives. You will not only learn about the famous pharaohs, but you will also meet infamous pharaohs, maybe for the first time.

Purchase your copy from Amazon and write a review about it here for other visitors, please.

Queen Hatshepsut. 18th Dynasty

(Don't forget to sign up for the FREE Egyptology course from Ancient Egypt History)

(18th Dynasty, part VII)

Queen Hatshepsut

(18th Dynasty, part VII)

|

Birth name: Hat-shepsut (Foremost of Noble Ladies)

Throne name: Maat-ka-re (Truth is the Soul of Ra)

Father: Tuthmosis I

Mother: Ahmose

Husband: Tuthmosis II

Daughter: Neferure

Burial: Tomb KV 20, Valley of the Kings (Thebes)

|

As Tuthmosis II had realized early on, Hatshepsut was a strong-willed woman who would not let anyone or anything stand in her way. By Year 2 of her co-regency with the child king Tuthmosis III she begun her policy to subvert his position. Initially, she had been content to be represented in reliefs standing behind Tuthmosis III and to be identified simply by her titles as queen and 'great king's wife' of Tuthmosis II. This changed as she gathered support from the highly pIaced officials, and it was not long before she began to build her splendid mortuary temple in the bay of the cliffs at Deir el-Bahari.

Constructed under the supervision of the queen's steward Senenmut - who was to rise to the highest offices during her reign - Hatshepsut's temple took its basic inspiration from the 12th Dynasty temple of Mentuhotep, adjacent to the site on the south. The final plan of the temple made it unique in Egyptian architecture: built largely of limestone, it rose in three broad, colonnade-fronted terraces to a central rock-cut sanctuary on the upper terrace. The primary dedication" was to Amon but there were also smaller shrines to Hathor (who earlier small cave shrine on the site) and Anubis, respectively located on the south and north sides of the second terrace. A feature of the temple was its alignment to the east directly with the great temple of Amon across the Nile at Karnak.

Constructed under the supervision of the queen's steward Senenmut - who was to rise to the highest offices during her reign - Hatshepsut's temple took its basic inspiration from the 12th Dynasty temple of Mentuhotep, adjacent to the site on the south. The final plan of the temple made it unique in Egyptian architecture: built largely of limestone, it rose in three broad, colonnade-fronted terraces to a central rock-cut sanctuary on the upper terrace. The primary dedication" was to Amon but there were also smaller shrines to Hathor (who earlier small cave shrine on the site) and Anubis, respectively located on the south and north sides of the second terrace. A feature of the temple was its alignment to the east directly with the great temple of Amon across the Nile at Karnak.

The queen legitimizes her rule

Hatshepsut recorded that she had built her mortuary temple as a 'garden for my father Amon', Certainly, it was a garden, with small trees and shrubs lining the entrance ramps to the temple, Her focus on Amon was strengthened in the temple by a propaganda relief, known as the 'birth relief', on the walls of the northern half of the middle terrace, Here Amon is shown visiting Hatshepsut's mother, Queen Ahmose, while nearby are the appropriate deities of childbirth (the ram-headed Khnum and the frog-headed goddess Heqet) and the seven 'fairy-god mother' Hathors, The thrust of all this was to emphasize that she, Hatshepsut, had been deliberately conceived and chosen by Amon to be king. She was accordingly portrayed with all the regalia of kingship, even down to the official royal false beard.

To symbolize her new position as king of Egypt, Hatshepsut took the titles of the Female Horus Wosretkau, 'King of Upper and Lower Egypt'; Maat-ka-re, 'Truth is the Soul of Re'; and Khnemetamun Hatshepsut, 'She who embraces Amon, the foremost of women'. Her coronation as a child in the presence of the gods is represented in direct continuation of the birth relief at Deir el-Bahari, subsequently confirmed by Atum at Heliopolis, The propaganda also indicated that she had been crowned before the court in the presence of her father Tuthmosis I who, according to the inscription, deliberately chose New Year's Day as an auspicious day for the event! The whole text is fictitious and, just like her miraculous conception, a political exercise. In pursuing this Hatshepsut makes great play upon the support of her long-dead but still highly revered father, Tuthmosis 1.

Temples and trading

The cult of Amon had gradually gained in importance during the Middle Kingdom under the patronage of the princes of Thebes. Now the more powerful New Kingdom kings associated the deity with their own fortunes. Hatshepsut had built her mortuary temple for Amon on the west bank, and further embellished the god's huge temple on the bank. Her great major-domo, Senenmut, was heavily involved in all her building works and was also responsible for the erection of a panir of red granite obelisks to the god at Karnak. Their removal from the quarries at Aswan is recorded in inscriptions there, while their actual transport butt-ended on low rafts calculated to be over 300 ft (100 m) long and 100 ft (30 m) wide, is represented in reliefs at the Deir el-Bahari temple a second pair was cut later at Aswan and erected at Karnak under the direction of Senenmut's colleague, Amunhotep; one of them still stands in the temple.

The queen did not, however, build only to the greater glory of Amon at Thebes: there are many records of her restoring temples in areas of Middle Egypt that had been left devastated under the Hyksos.

While Hatshepsut is not known for her military prowess, her reign is noted for its trading expeditions, particularly to the land of Punt (probably northern Somalia or Djibouti) - a record of which is carved on the walls of her temple. It shows the envoys setting off down the Red Sea (with fish accurately depicted in the water) and later their arrival in Punt, where they exchange goods and acquire the fragrant incense trees. Other trading and explorative excursions were mounted to the turquoise mines of Sinai, especially to the area of Serabit el-Khadim, where Hatshepsut's name has been recorded.

The cult of Amon had gradually gained in importance during the Middle Kingdom under the patronage of the princes of Thebes. Now the more powerful New Kingdom kings associated the deity with their own fortunes. Hatshepsut had built her mortuary temple for Amon on the west bank, and further embellished the god's huge temple on the bank. Her great major-domo, Senenmut, was heavily involved in all her building works and was also responsible for the erection of a panir of red granite obelisks to the god at Karnak. Their removal from the quarries at Aswan is recorded in inscriptions there, while their actual transport butt-ended on low rafts calculated to be over 300 ft (100 m) long and 100 ft (30 m) wide, is represented in reliefs at the Deir el-Bahari temple a second pair was cut later at Aswan and erected at Karnak under the direction of Senenmut's colleague, Amunhotep; one of them still stands in the temple.

The queen did not, however, build only to the greater glory of Amon at Thebes: there are many records of her restoring temples in areas of Middle Egypt that had been left devastated under the Hyksos.

While Hatshepsut is not known for her military prowess, her reign is noted for its trading expeditions, particularly to the land of Punt (probably northern Somalia or Djibouti) - a record of which is carved on the walls of her temple. It shows the envoys setting off down the Red Sea (with fish accurately depicted in the water) and later their arrival in Punt, where they exchange goods and acquire the fragrant incense trees. Other trading and explorative excursions were mounted to the turquoise mines of Sinai, especially to the area of Serabit el-Khadim, where Hatshepsut's name has been recorded.

Queen Hatshepsut's tomb

Hatshepsut had her tomb dug in the Valley of the Kings (KV 20) by her vizier and High Priest of Amon, Hapuseneb. She had previously had a tomb cut for herself as queen regnant under Tuthmosis II, its entrance 220 ft (72 m) up a 350-ft (91-m) cliff face in a remote valley west of the Valley of the Kings. This was found by locals in 1916 and investigated by Howard Carter in rather dangerous circumstances. The tomb had never been used and still held the sandstone sarcophagus inscribed for the queen. Carter wrote: 'as a king, it was clearly necessary for her to have her tomb in The Valley like all other kings - as a matter of fact I found it there myself in 1903 - and the present tomb was abandoned. She would have been better advised to hold to her original plan. In this secret spot her mummy would have had a reasonable chance of avoiding disturbance: in The Valley it had none. A king she would be, and a king's fate she shared.'

Hatshepsut had her tomb dug in the Valley of the Kings (KV 20) by her vizier and High Priest of Amon, Hapuseneb. She had previously had a tomb cut for herself as queen regnant under Tuthmosis II, its entrance 220 ft (72 m) up a 350-ft (91-m) cliff face in a remote valley west of the Valley of the Kings. This was found by locals in 1916 and investigated by Howard Carter in rather dangerous circumstances. The tomb had never been used and still held the sandstone sarcophagus inscribed for the queen. Carter wrote: 'as a king, it was clearly necessary for her to have her tomb in The Valley like all other kings - as a matter of fact I found it there myself in 1903 - and the present tomb was abandoned. She would have been better advised to hold to her original plan. In this secret spot her mummy would have had a reasonable chance of avoiding disturbance: in The Valley it had none. A king she would be, and a king's fate she shared.'

Hatshepsut's second tomb was located at the foot of the cliffs in the eastern corner of the Valley of the Kings. The original intention seems to have been for a passage to be driven through the rock to locate the burial chamber under the sanctuary of the queen's temple on the other side of the cliffs. In the event, bad rock was struck and the tomb's plan takes a great U-turn back on itself to a burial chamber that contained two yellow quartzite sarcophagi, one inscribed for Tuthmosis I and the other for Hatshepsut as king (p. 101). The queen's mummy has never been identified, although it has been suggested that a female mummy rediscovered in 1991 in KV 21 (the tomb of Hatshepsut's nurse) might have been her body.

Hatshepsut died in about 1483 BC. Some suggest that Tuthmosis III, kept so long in waiting, may have had a hand in her death. Certainly he hated her enough to destroy many of the queen's monuments and those of her closest adherents. Perhaps the greatest posthumous humiliation she was to suffer, however, was to be omitted from the carved king lists: her reign was too disgraceful an episode to be recorded.

Check The Mortuary Temple of Queen Hatshepsut in details

Check The Mortuary Temple of Queen Hatshepsut in details

If you want to learn more about the Pharaohs of ancient Egypt, you will love the book Chronicle of the Pharaohs: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt (The Chronicles Series)

This book tells you the complete story of ancient Egypt through its pharaohs' lives. You will not only learn about the famous pharaohs, but you will also meet infamous pharaohs, maybe for the first time.

Purchase your copy from Amazon and write a review about it here for other visitors, please.

Akhenaten, Amenhotep IV. 18th Dynasty.

Posters of Akhentaten

You want to show respect and love to the great revolutionary pharaoh Akhenaten? You can get one of these posters to hang on your wall! They are very cheap and they are very beautiful. I believe the average poster size is 18" x 24" (inches). And the average price is $20 to $40 US Dollars. However, prices and sizes will vary, just take a look at these outstanding posters that could bring both your wall and Akhenaten to life!

Just in case you are wondering, the two gray posters with a sun disk, represent the relatively-new revolutionary religion that Akhenaten has created with his wife (Nefertiti, who is also there with him in three of these posters). Akhenaten and Nefertiti have changed the country's religious views into monotheist views. Their god Aten (the sun-disk god) was praised and a new city (called Akhetaten or Amarna) was just built for that cause, and then the capital was moving from Thebes to Akhetaten for a while.

Here are a few posters of Amarna:

Amenhotep IV - better known as Akhenaten, the new name he took early on in his reign - ushered in a revolutionary period in Egypt history. The Amarna Interlude, as it is often called, saw the removal of the seat of government to a short-lived new capital city, Akhetaten (modern el-Amarna, a new book is going to be released in a few weeks, make sure to pre-order it) , the introduction of a new art style, and the elevation of the cult of the sun disc, the Aten, to pre-eminent status in Egyptian religion. This last heresy in particular was to bring down on Akhenaten and his immediate successors the opprobrium of later kings.

, the introduction of a new art style, and the elevation of the cult of the sun disc, the Aten, to pre-eminent status in Egyptian religion. This last heresy in particular was to bring down on Akhenaten and his immediate successors the opprobrium of later kings.

It is evident from the art of the Amarna period that the court officially emulated the king's unusual physical characteristics. Thus individuals such as the young princesses are endowed with elongated skulls and excessive adiposity, while Bek - the Chief Sculptor and Master of Works - portrays himself in the likeness of his king with pendulous breasts and protruding stomach. On a stele now in Berlin Bek states that he was taught by His Majesty and that the court sculptors were instructed to represent what they saw. The result is a realism that breaks away from the rigid formality of earlier official depictions although naturalism is very evident in earlier, unofficial art.

The power behind Akhenaten's throne?

Although the famous bust of Nefertiti in Berlin shows her with an elongated neck, the queen is not subject to quite the same extreme as others in Amarna art, by virtue of being elegantly female. Indeed there are several curious aspects of Nefertiti's representation. early years of Akhenaten's reign, for instance, Nefertiti was an unusually prominent figure in official art, dominating the scenes carved on blocks of the temple to the Aten at Karnak. One such block shows her in the age-old warlike posture of pharaoh grasping captives by the hair and smiting them with a mace - hardly the epitome of the peaceful queen and mother of six daughters. Nefertiti evidently played a far more prominent part in her husband's rule than was the norm.

Tragedy seems to have struck the royal family in about Year 12 with the death in childbirth of Nefertiti's second daughter, Mekytaten, it is probably she who is shown in a relief in the royal tomb with her stricken parents beside her supine body, and a nurse standing nearby holding a baby. The father of the infant was possibly Akhenaten, since he is also known to have married two other daughters, Merytaren (not to be confused with Mekytaten) and Akhesenpaaten (later to Tutankhamun's wife).

Nefertiti appears to have died soon after Year 12, although some suggest that she was disgraced because her name was replaced in several instances by that of her daughter Merytaten, who succeed her as 'Great Royal Wife'. The latter bore a daughter called Merytaten-tasherit (Merytaten the Younger), also possibly fathered by Akhentaten. Merytaten was to become the wife of Smenkhkare, Akhenatten's brief successor. Nefertiti was buried in the royal tomb at Amarna, judging by the evidence of a fragment of an alabaster ushabti figure bearing her cartouch found there in the early 1930s.

Akhetaten (or el-Amarna as it is now known) is an important site because it was occupied neither before nor after its short life as capital under Akhenaten. It is ringed by a natural amphitheater of cliffs on both sides of the Nile and delineated by a series of 15 large stele carved in the rock around its perimeter. On the stele, reliefs show Akhenaten adoring his god in the company of his wife and various of their six daughters, and give instructions that all should be buried within the city's sacred precincts. To this end a royal tomb was cut in a remote wadi situated mid-way between the tombs of the nobbles, now referred to the North and the South tombs.

Akhenaten's resting place

Akhenaten died c. 1334, probably in his 16th regnal year. Evidence found by Professor Geoffrey Martin during re-excavation of the royal tomb at Amarna showed that blocking had been put in place in the burial chamber, suggesting that Akhenaten was buried there initially. Others do not believe that the tomb was used, however, in view of the heavily smashed fragments of his sarcophagus and canopic jars r recovered from it, and also the shattered examples of his ushabtis - found not only in the area of the tomb but also by Petrie in the city.

What is almost certain is that his body did not remain at Amarna. A burnt mummy seen outside the royal tomb in the 1880s, and associated with Egyptian jewelry from the tomb (including a small gold finger ring with Nefertiti's cartouch), was probably Coptic, as was other Egyptian jewelry nearby. Akhenaten's adherents would not have left his body to be despoiled by his enemies once his death and the return to orthodoxy unleashed a backlash of destruction. They would have taken it to a place of safety - and where better to hide it than in the old royal burial ground at Thebes where enemies would never dream of seeking it?

You want to show respect and love to the great revolutionary pharaoh Akhenaten? You can get one of these posters to hang on your wall! They are very cheap and they are very beautiful. I believe the average poster size is 18" x 24" (inches). And the average price is $20 to $40 US Dollars. However, prices and sizes will vary, just take a look at these outstanding posters that could bring both your wall and Akhenaten to life!

Just in case you are wondering, the two gray posters with a sun disk, represent the relatively-new revolutionary religion that Akhenaten has created with his wife (Nefertiti, who is also there with him in three of these posters). Akhenaten and Nefertiti have changed the country's religious views into monotheist views. Their god Aten (the sun-disk god) was praised and a new city (called Akhetaten or Amarna) was just built for that cause, and then the capital was moving from Thebes to Akhetaten for a while.

Here are a few posters of Amarna:

Amenhotep IV - better known as Akhenaten, the new name he took early on in his reign - ushered in a revolutionary period in Egypt history. The Amarna Interlude, as it is often called, saw the removal of the seat of government to a short-lived new capital city, Akhetaten (modern el-Amarna, a new book is going to be released in a few weeks, make sure to pre-order it)

The young prince was at least the second son of Amenhotep III by his chief wife, Tiy: an elder brother, prince Tuthmosis, had died prematurely (strangely, a whip bearing his name was found in Tutankhamun's tomb). There is some controversy over whether or not the old king took his son into partnership on the throne in a co-regency - there are quite strong arguments both for and against. A point in favour of a co-regency is the appearance during the latter years of Amenhotep III's reign of artistic styles that are subsequently seen as part of the 'revolutionary Amarna art introduced by Akhenaten; on the other hand, both traditional' and 'revolutionary' art styles could easily have coexisted during the early years of Akhenaten's reign. At any rate, if there had been a coregency, it would not have been for longer than the short period before the new king assumed his preferred name of Akhenaten ('Servant of the Aten') in Year 5.

The beginning of Akhenaten's reign marked no great discontinuity with that of his predecessors. Not only was he crowned at Karnak (temple of the god Amun) but, like his father, he married a lady of non-royal blood, Nefertiti, the daughter of the vizier Ay. Ay seems to have been a brother of Queen Tiy and a son of Yuya and Tuya. Nefertiti's mother is not known; she may have died in c;hildbirth or shortly afterwards, since Nefertiti seems to have been brought up by another wife of Ay named Tey, who would then be her stepmother.

Akhenaten and the cult of the Aten

There can be httle doubt that the new king was far more of a thinker and philosopher than his forebears. Amenhotep III had recognized the growing power of the priesthood of Amun and had sought to curb it; his son was to take the matter a lot further by introducing a new monotheistic cult of sun-worship that was incarnate in the sun's disc, the Aten.

This was not in itself a new idea: as a relatively minor aspect of the sun god Re-Harakhte, the Aten had been venerated in the Old Kingdom and a large scarab of Akhenaten's grandfather Tuthmosis IV (now in the British Museum) has a text that mentions the Aten. Rather Akhenaten's innovation was to worship the Aten in its own right Portrayed as a solar disc whose protective rays terminated in hands holding the ankh hieroglyph for life, the Aten was accessible only to Akhenaten, thereby obviating the need for an intermediate priesthood.

At first, the king built a temple to his god Aten immediately outside the east gate of the temple of Amun at Karnak, but clearly the coexis tence of the two cults could not last. He therefore proscribed the cult of Amun, closed the god's temples, took over the revenues and, to make a complete break, in Year 6 moved to a new capital in Middle Egypt, half way between Memphis and Thebes. It was a virgin site, not previously dedicated to any other god or goddess, and he named it Akhetaten - The Horizon of the Aten. Today the site is known as el-Amarna.

In the tomb of Ay, the chief minister of Akhenaten (and later to become king after Tutankhamun's death, p. 136), occurs the longest and best rendition of a composition known as the 'Hymn to the Aten', said to have been written by Akhenaten himself. Quite moving in itself as a piece of poetry, its similarity to, and possible source of the concept in, Psalm 104 has long been noted. It sums up the whole ethos of the Aten cult and especially the concept that only Akhenaten had access to the god: 'Thou arisest fair in the horizon of Heaven, 0 Living Aten, Beginner of Life ... there is none who knows thee save thy son Akhenaten. Thou hast made him wise in thy plans and thy power.' No longer did the dead call upon Osiris to guide them through the afterworld, for only through their adherence to the king and his intercession on their behalf could they hope to live beyond the grave.

According to present evidence, however, it appears that it was only the upper echelons of society which embraced the new religion with any fervour (and perhaps that was only skin deep). Excavations at .'Amarna have indicated that even here the old way of religion continued among the ordinary people. On a wider scale, throughout Egypt, the new cult does not seem to have had much effect at a common level except, of course, in dismantling the priesthood and closing the temples; but then the ordinary populace had had little to do with the religious establishment anyway, except on the high days and holidays when the god's statue would be carried in procession from the sanctuary outside the great temple walls.

The standard bureaucracy continued its endeavours to run the country while the king courted his god. Cracks in the Egyptian empire may have begun to appear in the later years of the reign of Amenhotep III; at any rate they became more evident as Akhenaten increasingly left government and diplomats to their own devices. Civil and military authority came under two strong characters: Ay, who held the title 'Father of the God' land was probably Akhenaten's father-in-IawL and the general Horemheb (also Ay's son-in-law since he married Ay's daughter Mutnodjme, sister of Nefertiti). Both men were to become pharaoh before the 18th Dynasty ended. This redoubtable pair of closely related high officials no doubt kept everything under control in a discreet manner while Akhenaten pursued his own philosophical and religious interests.

The new artistic style of Akhenaten

The beginning of Akhenaten's reign marked no great discontinuity with that of his predecessors. Not only was he crowned at Karnak (temple of the god Amun) but, like his father, he married a lady of non-royal blood, Nefertiti, the daughter of the vizier Ay. Ay seems to have been a brother of Queen Tiy and a son of Yuya and Tuya. Nefertiti's mother is not known; she may have died in c;hildbirth or shortly afterwards, since Nefertiti seems to have been brought up by another wife of Ay named Tey, who would then be her stepmother.

Akhenaten and the cult of the Aten

This was not in itself a new idea: as a relatively minor aspect of the sun god Re-Harakhte, the Aten had been venerated in the Old Kingdom and a large scarab of Akhenaten's grandfather Tuthmosis IV (now in the British Museum) has a text that mentions the Aten. Rather Akhenaten's innovation was to worship the Aten in its own right Portrayed as a solar disc whose protective rays terminated in hands holding the ankh hieroglyph for life, the Aten was accessible only to Akhenaten, thereby obviating the need for an intermediate priesthood.

At first, the king built a temple to his god Aten immediately outside the east gate of the temple of Amun at Karnak, but clearly the coexis tence of the two cults could not last. He therefore proscribed the cult of Amun, closed the god's temples, took over the revenues and, to make a complete break, in Year 6 moved to a new capital in Middle Egypt, half way between Memphis and Thebes. It was a virgin site, not previously dedicated to any other god or goddess, and he named it Akhetaten - The Horizon of the Aten. Today the site is known as el-Amarna.

In the tomb of Ay, the chief minister of Akhenaten (and later to become king after Tutankhamun's death, p. 136), occurs the longest and best rendition of a composition known as the 'Hymn to the Aten', said to have been written by Akhenaten himself. Quite moving in itself as a piece of poetry, its similarity to, and possible source of the concept in, Psalm 104 has long been noted. It sums up the whole ethos of the Aten cult and especially the concept that only Akhenaten had access to the god: 'Thou arisest fair in the horizon of Heaven, 0 Living Aten, Beginner of Life ... there is none who knows thee save thy son Akhenaten. Thou hast made him wise in thy plans and thy power.' No longer did the dead call upon Osiris to guide them through the afterworld, for only through their adherence to the king and his intercession on their behalf could they hope to live beyond the grave.

According to present evidence, however, it appears that it was only the upper echelons of society which embraced the new religion with any fervour (and perhaps that was only skin deep). Excavations at .'Amarna have indicated that even here the old way of religion continued among the ordinary people. On a wider scale, throughout Egypt, the new cult does not seem to have had much effect at a common level except, of course, in dismantling the priesthood and closing the temples; but then the ordinary populace had had little to do with the religious establishment anyway, except on the high days and holidays when the god's statue would be carried in procession from the sanctuary outside the great temple walls.

The standard bureaucracy continued its endeavours to run the country while the king courted his god. Cracks in the Egyptian empire may have begun to appear in the later years of the reign of Amenhotep III; at any rate they became more evident as Akhenaten increasingly left government and diplomats to their own devices. Civil and military authority came under two strong characters: Ay, who held the title 'Father of the God' land was probably Akhenaten's father-in-IawL and the general Horemheb (also Ay's son-in-law since he married Ay's daughter Mutnodjme, sister of Nefertiti). Both men were to become pharaoh before the 18th Dynasty ended. This redoubtable pair of closely related high officials no doubt kept everything under control in a discreet manner while Akhenaten pursued his own philosophical and religious interests.

The new artistic style of Akhenaten

It is evident from the art of the Amarna period that the court officially emulated the king's unusual physical characteristics. Thus individuals such as the young princesses are endowed with elongated skulls and excessive adiposity, while Bek - the Chief Sculptor and Master of Works - portrays himself in the likeness of his king with pendulous breasts and protruding stomach. On a stele now in Berlin Bek states that he was taught by His Majesty and that the court sculptors were instructed to represent what they saw. The result is a realism that breaks away from the rigid formality of earlier official depictions although naturalism is very evident in earlier, unofficial art.

The power behind Akhenaten's throne?

Although the famous bust of Nefertiti in Berlin shows her with an elongated neck, the queen is not subject to quite the same extreme as others in Amarna art, by virtue of being elegantly female. Indeed there are several curious aspects of Nefertiti's representation. early years of Akhenaten's reign, for instance, Nefertiti was an unusually prominent figure in official art, dominating the scenes carved on blocks of the temple to the Aten at Karnak. One such block shows her in the age-old warlike posture of pharaoh grasping captives by the hair and smiting them with a mace - hardly the epitome of the peaceful queen and mother of six daughters. Nefertiti evidently played a far more prominent part in her husband's rule than was the norm.

Tragedy seems to have struck the royal family in about Year 12 with the death in childbirth of Nefertiti's second daughter, Mekytaten, it is probably she who is shown in a relief in the royal tomb with her stricken parents beside her supine body, and a nurse standing nearby holding a baby. The father of the infant was possibly Akhenaten, since he is also known to have married two other daughters, Merytaren (not to be confused with Mekytaten) and Akhesenpaaten (later to Tutankhamun's wife).

Nefertiti appears to have died soon after Year 12, although some suggest that she was disgraced because her name was replaced in several instances by that of her daughter Merytaten, who succeed her as 'Great Royal Wife'. The latter bore a daughter called Merytaten-tasherit (Merytaten the Younger), also possibly fathered by Akhentaten. Merytaten was to become the wife of Smenkhkare, Akhenatten's brief successor. Nefertiti was buried in the royal tomb at Amarna, judging by the evidence of a fragment of an alabaster ushabti figure bearing her cartouch found there in the early 1930s.

Akhetaten (or el-Amarna as it is now known) is an important site because it was occupied neither before nor after its short life as capital under Akhenaten. It is ringed by a natural amphitheater of cliffs on both sides of the Nile and delineated by a series of 15 large stele carved in the rock around its perimeter. On the stele, reliefs show Akhenaten adoring his god in the company of his wife and various of their six daughters, and give instructions that all should be buried within the city's sacred precincts. To this end a royal tomb was cut in a remote wadi situated mid-way between the tombs of the nobbles, now referred to the North and the South tombs.

None of the tombs was ever finished and probably few of them were actually occupied. If they were, loving relatives almost certainly rapidly removed the bodies immediately after the king's death, because of the backlash unleashed against him and his monuments.

The actual city was a linear development along part of the east bank, strentching back not very far into the desert where a number of small sun kiosks were located on the routes to the tombs. A broad thoroughfare, sometimes called the King's Road or Royal Avenue, linked the two ends of the city and was flanked by a series of official builders, including the royal palace (Great Palace), the new style open-air temple to the Aten (the Great Temple), and administrative offices. The Great Palace was probably a ceremonial center rather than a royal residence; the king and his family may have lived in the North Palace.The houses of the upper classes (mainly young nobles who had accompanied the king in his radical move) were arranged on an open plan, not crowded together as is usually found in the ancient Near East. Most were lavish buildings, with pools and gardens. The overall impression was that of a "garden city".

The whole essence of the court and life at Amarna revolved around the king and his god the Aten. Everywhere the royal family appeared they were shown to be under the protection of the Aten's rays. Reliefs in the tombs of the nobles at the site all focused on the king and through him the Aten.

Great scenes covered the walls and continued, unlike earlier and later tomb decoration, from wall to wall. The king, usually accompanied by Nefertiti and a number of their daughters, dominated the walls, normally in scenes showing them proceeding to the temple of the Aten in chariots drawn by spirited and richly caparisoned horses. Small vignettes occur of men drawing water using shadufs (the ancient bucket and wieghted pole method that until recently was a common sight in Egypt, but is now fast disappearing); fat cattle are fed in their byres; blind musicians, their faces beautifully observed, sing the praises of Akhenaten and the Aten. Everything is alive and thriving under Akhenaten's patronage through the beneficence of the Aten.

Akhenaten, Male or Female?

When the tomb of Akhenaten was rediscovered at Amarna in the early 1880s, portraits of the royal couple were at first thought to represent two females, by virtue of Akhenaten's curious androgynous shape. One explanation for the king's unusual figure was that he suffered from a tumour of the pituitary gland, resulting in what is known as frohlich syndrome. Certain well-known effects of this disorder seem to be very evident in representations of Akhenaten; skull malformation; and lantern-like jaw; the head looking over-heavy on an elongated neck; excessive fat in areas that are more indicative of the female form, e.g. around the thighs, buttocks and breasts; and spindly legs. A side-effect of this condition, however, is infertility, and critics have pointed out that Akhenaten would have been unable to father the six daughters with whom he is so frequently shown on the other hand, he could have been struck by the illness at a later stage in his life.

Akhenaten's resting place

Akhenaten died c. 1334, probably in his 16th regnal year. Evidence found by Professor Geoffrey Martin during re-excavation of the royal tomb at Amarna showed that blocking had been put in place in the burial chamber, suggesting that Akhenaten was buried there initially. Others do not believe that the tomb was used, however, in view of the heavily smashed fragments of his sarcophagus and canopic jars r recovered from it, and also the shattered examples of his ushabtis - found not only in the area of the tomb but also by Petrie in the city.

What is almost certain is that his body did not remain at Amarna. A burnt mummy seen outside the royal tomb in the 1880s, and associated with Egyptian jewelry from the tomb (including a small gold finger ring with Nefertiti's cartouch), was probably Coptic, as was other Egyptian jewelry nearby. Akhenaten's adherents would not have left his body to be despoiled by his enemies once his death and the return to orthodoxy unleashed a backlash of destruction. They would have taken it to a place of safety - and where better to hide it than in the old royal burial ground at Thebes where enemies would never dream of seeking it?

Names, Family and Burial of Akhenaten

Akhenaten's Birth name: Amen-hotep (Amon is Pleased)

Also known as: Amenhotpe IV, Amenophis IV (Greek)

Adopted name (year 5) Akh-en-aten (Servant of the Aten)

Akhenaten's throne name: Nefer-kheperu-re (Beautiful are the Manifestations of Ra)

Akhenaten's father: Amenhotep III

Akhenaten's mother: Tiy

Akhenaten's wives: Nefertiti, Merytaten, Kiya, Mekytaten, Ankhesenpaaten

Akhenaten's son: Tutankhamun

Akhenaten's daughters: Merytaten, Mekytaten, Ankhesenpaaten, Merytaten-tasherit and others

Akhenaten's burial: Akhetaten (el-Amarna) subsequently, Valley of the Kings, Thebes.

Tomb of Kheruef Plan - Tombs of the Nobles - Luxor, Egypt. Part XVI

Tombs of the Nobles, Luxor, Egypt.

Kheruef was steward to the Great Royal Wife Queen Tiy at the crucial period of the 18th Dynasty just before Amon was dethroned by Akhenaten, The tomb was never completed but the murals are carved in exquisite high relief.

The outer courtyard contains various other tombs and a wall has been constructed to preserve the reliefs of Kheruef. On the left-hand wall are delightful scenes from the Sed festival, the 30-year Jubilee of the Pharaoh. Amenhotep III and Queen Tiy are seated with Hathor behind them (a) watching a processional dance in their honour. Further along the wall (b) they leave the palace with eight slim princesses walking in pairs and bearing jars of sacred water.

The outer courtyard contains various other tombs and a wall has been constructed to preserve the reliefs of Kheruef. On the left-hand wall are delightful scenes from the Sed festival, the 30-year Jubilee of the Pharaoh. Amenhotep III and Queen Tiy are seated with Hathor behind them (a) watching a processional dance in their honour. Further along the wall (b) they leave the palace with eight slim princesses walking in pairs and bearing jars of sacred water.At (c) delightful carvings of the ceremonial dance suggest a ritual of rebirth of life on the earth and include a jumping bird, a flying bird and a monkey. In the lower row are musicians with flutes and drums. Towards the end of the wall (d) is a sketch of the high priest and the text describes the celebration. The right-hand section of the wall is somewhat damaged. At (c) Amenhotep III is portrayed with his sixteen princes. With Queen Tiy he watches the erection of a column symbolizing the god Osiris (f). At (g) the Pharaoh and Queen Tiy are shown with the deceased nobleman behind them. Beneath the trio are the conquered cities.

The other nobleman of this era, when the royal capital was being shifted to Tel el Amarna, was Ramose. But while Ramose followed his master to the new capital, Kheruef remained in Thebes with the royal mother.

Tomb of Ineni - Nobles Tombs - Luxor Egypt. Part XIV

Also called Enne, This was the architect who excavated the first tomb in the Valley of the Kings, that of Thutmose I. His tomb comprises a main chamber, the facade of which is formed of pillars which carry their

murals on the rear faces, and a corridor.

Three of the square pillars carry particularly interesting murals.

The first (a) is a hunting scene with a rearing hyena biting a broken arrow as a dog rushes the wounded creature from the rear and gazelles flee. The second (b) shows Ineni's country house and he and his wife are seen in the arbour (damaged) from whence he orders his gardener round the walled estate. On the third pillar (c) Ineni can be seen before a sumptuous feast.

The first (a) is a hunting scene with a rearing hyena biting a broken arrow as a dog rushes the wounded creature from the rear and gazelles flee. The second (b) shows Ineni's country house and he and his wife are seen in the arbour (damaged) from whence he orders his gardener round the walled estate. On the third pillar (c) Ineni can be seen before a sumptuous feast. On the left-hand rear wall of the first chamber (d) Ineni receives tributes from swarthy Nubians including two women who carry their babies on their backs (top row). Below he receives contributions from the peasants. This part of the mural is squared up for the draughtsman. On the right-hand wall (e) is a scene in poor condition of Ineni and his pet dog watching a parade of the estate animals including sheep, goats, flamingos and geese.

On the left-hand rear wall of the first chamber (d) Ineni receives tributes from swarthy Nubians including two women who carry their babies on their backs (top row). Below he receives contributions from the peasants. This part of the mural is squared up for the draughtsman. On the right-hand wall (e) is a scene in poor condition of Ineni and his pet dog watching a parade of the estate animals including sheep, goats, flamingos and geese.On the left-hand wall of the rear corridor (f) Ineni and his wife receive offerings. On the right-hand wall (g) are more funerary scenes and offerings. The roof is decorated.

In the niche at the rear are four seated statues of Ineni's wife Thuau, Ineni himself, his father Ineni, and his sister Aahhotep. (from left to right)

Tomb of Amenemheb Plan - Nobles Tombs - Luxor, Egypt. Part IX

Tombs of the Nobles, Luxor, Egypt.

This tomb has a line of pillars in the first chamber and side chambers leading off the main corridor directly behind it. It is important historically because Amenemheb was the military commander of Thutmose III, and not only does his tomb record his part in the Pharaoh's important Asiatic campaigns, but it gives exact information of the length of his reign and those of his predecessors.

Amenemheb is recorded as having accomplished two feats of unusual daring. One was during the battle of Kadesh on the Orontes when, just before the clash of arms as the opposing armies were poised and ready, the prince of Kadesh released a mare who galloped straight for the battle lines of the Egyptian army. The plan was to break up the rank sand confuse the soldiers but Commander Amenemheb, ever on the alert, reportedly leapt from his chariot, pursued the mare, caught it and promptly slew it.

The second experience took place on the return march from Asia Minor when near the Euphrates the Pharaoh was suddenly in danger of being run down by a herd of wild elephants. Amenemheb not only managed to divert the danger and save his master from a nasty fate but apparently struck off the trunk of the leader of the herd while balancing precariously between two rocks!

The second experience took place on the return march from Asia Minor when near the Euphrates the Pharaoh was suddenly in danger of being run down by a herd of wild elephants. Amenemheb not only managed to divert the danger and save his master from a nasty fate but apparently struck off the trunk of the leader of the herd while balancing precariously between two rocks!Naturally such a brave and dutiful warrior should be justly rewarded by his Pharaoh for his bravery and such noble s as Amenemheb received part of the booty, decorations, and in special cases even land in recognition of their services.

Three walls in this tomb are especially note worthy. The first is in the main chamber (1) on the rear right-hand wall (a) . This is the record of Thutmose III's Asiatic campaigns, his length of reign, etc., as well as a record of Amenemheb's military honors. Near the bottom of the wall Syrians bring tribute. They wear white garments with colored braiding and there are talkative children among them.

In the chamber leading off the corridor to the right (2) is a scene on the left-hand wall (b) of a feast in progress with abundant food and drink. Servants bring bunches of flowers. The guests, relaxing in comfortable chairs or squatting on stools, are offered refreshments and the ladies in the second row all hold lotus flowers in their hands, while around their necks and in their hair they have blossoms. Attendants hold staffs wreathed and crowned with flowers. Lower on the wall are harp, flute and lute-players. It is a cheerful and lively representation.

In the rear corridor on the left-hand wall (c) is the private garden of Commander Amenemheb. Fish swim in a pool surrounded by plants. The deceased and his wife are presented with flowers.

The funerary scenes are found in the left-hand chamber (3) which leads off the rear corridor.

Tomb of Rekhmire Plan - Tombs of the Nobles, Luxor, Egypt. Part VII

Tomb of the Nobles, Luxor, Egypt.

Rekhmire was vizier under Thutmose III and his son Amenhotep II. The tomb follows the regular style of the 18th Dynasty nobles' tombs, comprising a narrow, oblong first chamber and a long corridor opposite the entrance. But this corridor rapidly gains in height to the rear of the tomb and runs Into the rock. It was inhabited by a farming family for many years and the wall decorations have suffered at their hands. The tomb is a memorial to personal greatness and a revelation on law, taxation and numerous industries. Professor Breasted described It as "the most Important private monument of the Empire".

Rekhmire was an outstanding vizier who was entrusted with a great many duties. There was nothing, he wrote of himself in an inscription, of which he was ignorant in heaven, on earth or in any part of the underworld. One of the most important scenes in the tomb is that on the left-hand wall of the first chamber near the corner (a). It shows the interior of a court of law in which tax evaders are brought to justice by the grand vizier himself. The prisoners are led up the central aisle, witnesses wait outside and at the foot of the judgement seat are four mats with rolled papyri.

Rekhmire was an outstanding vizier who was entrusted with a great many duties. There was nothing, he wrote of himself in an inscription, of which he was ignorant in heaven, on earth or in any part of the underworld. One of the most important scenes in the tomb is that on the left-hand wall of the first chamber near the corner (a). It shows the interior of a court of law in which tax evaders are brought to justice by the grand vizier himself. The prisoners are led up the central aisle, witnesses wait outside and at the foot of the judgement seat are four mats with rolled papyri. These are proof that written law existed in 1500 B.C. Messengers wait outside and others bow deeply as they enter the presence of the vizier.

These are proof that written law existed in 1500 B.C. Messengers wait outside and others bow deeply as they enter the presence of the vizier.Near the center of the opposite wall (b) Rekhmire performs his dual role of receiving taxes from officials who annually came with their dues, and receiving tributes from the vassal princes of Asia, the chiefs of Nubia,etc. The foreign gift-bearers are arranged in five rows: from the Land of Punt (dark skinned), from Crete (hearing vases of the distinctive Minoan type discovered on the island by Sir Arthur Evans) , from Nubia, from Syria, and men, women and children from the South. The diverse and exotic tributes range from panthers, apes and animal skins, to chariots, pearls and costly vases, to say nothing of an elephant and a bear.

The inner corridor gives an insight into the activities of the times. On the left-hand wall (c) Rekhmire supervises the delivery of corn, wine and cloth from the royal storehouses. He inspects carpenters, leather-workers, metal-workers and potters, who all came under his control. In the lower row is a somewhat damaged record for posterity of one of the most important tasks with which he was entrusted: supervising the construction of an entrance portal to the temple of Amon at Karnak. He held vigil over the manufacture of the raw material, the moulding of the bricks and their final use. Pylons and sphinxes, furniture and even household

The inner corridor gives an insight into the activities of the times. On the left-hand wall (c) Rekhmire supervises the delivery of corn, wine and cloth from the royal storehouses. He inspects carpenters, leather-workers, metal-workers and potters, who all came under his control. In the lower row is a somewhat damaged record for posterity of one of the most important tasks with which he was entrusted: supervising the construction of an entrance portal to the temple of Amon at Karnak. He held vigil over the manufacture of the raw material, the moulding of the bricks and their final use. Pylons and sphinxes, furniture and even householdutensils all came under his control. There are interesting scenes, to the left of the bottom row, of seated and standing statues being given final touches by the artist before polishing. The fascinating detail provides a pictorial treatise on the different industries of the times.

On the right-hand wall (d) Rekhmire may be seen at a table and there are traditional scenes of offerings before statues of the deceased, the deceased in a boat on a pond being towed by men on the bank, and a banquet with musicians and singers.

All the representations in this tomb show rhythm and free-posing, gesticulating and active figures. They are very different from the patterned group action with which we are familiar. The high premium traditionally set on balanced design was not lost. But the solid strings of people are gone, and with the break with the frieze the curtain is suddenly lifted on a picture of things as they really were: workers bending to mix mortar or squatting to carve a statue: a man who raises a bucket to his colleague's shoulder; another engrossed in carpentry; the elegant ladies of Rekhmire's household preparing for a social function with young female servants arranging their hair, anointing their limbs, bringing them jewelery. The message in these delightful murals is forceful and clear, with the dignified personage of the vizier himself towering over his subordinate sin administrative excellence.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Showing posts with label 18th Dynasty. Show all posts

Showing posts with label 18th Dynasty. Show all posts

Amenhotep III. 18th Dynasty

(Don't forget to sign up for the FREE Egyptology course from Ancient Egypt History)

(18th Dynasty, part XIII)

Chronicles of the Pharaohs

If you want to learn more about the Pharaohs of ancient Egypt, you will love the book Chronicle of the Pharaohs: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt (The Chronicles Series) .

.

This book tells you the complete story of ancient Egypt through its pharaohs' lives. You will not only learn about the famous pharaohs, but you will also meet infamous pharaohs, maybe for the first time.

Purchase your copy from Amazon and write a review about it here for other visitors, please.

(18th Dynasty, part XIII)

Amenhotep III's long reign of almost 40 years was one of the most prosperous and stable in Egyptian history. His great-grandfather, Tuthmosis III, had laid the foundations of the Egyptian empire by his campaigns into Syria, Nubia and Libya. Hardly any military activity was called for under Amenhotep III, and such little as there was, in Nubia, was directed by his son and viceroy of Kush, Merymose.

Amenhotep III was the son of Tuthmosis IV by one of his chief wives, Queen Mutemwiya. It is possible [though now doubted by some) that she was the daughter of the Mitannian king, Artatama, sent to the Egyptian court as part of a diplomatic arrangement to cement the alliance between the strong militarist state of Mitanni in Syria and

Egypt. The king's royal birth is depicted in a series of reliefs in a room on the east side of the temple of Luxor which Amenhotep III built for Amon. The creator god, the ramheaded Khnum of Elephantine, is seen fashioning the young king and his ka (spirit double) on a potter's wheel, watched by the goddess Isis. The god Amun is then led to his meeting with the queen by ibis-headed Thoth, god of wisdom. Subsequently, Amun is shown standing in the presence of the goddesses Hathor and Mut and nursing the child created by Khnum.

Amenhotep III was the son of Tuthmosis IV by one of his chief wives, Queen Mutemwiya. It is possible [though now doubted by some) that she was the daughter of the Mitannian king, Artatama, sent to the Egyptian court as part of a diplomatic arrangement to cement the alliance between the strong militarist state of Mitanni in Syria and

Egypt. The king's royal birth is depicted in a series of reliefs in a room on the east side of the temple of Luxor which Amenhotep III built for Amon. The creator god, the ramheaded Khnum of Elephantine, is seen fashioning the young king and his ka (spirit double) on a potter's wheel, watched by the goddess Isis. The god Amun is then led to his meeting with the queen by ibis-headed Thoth, god of wisdom. Subsequently, Amun is shown standing in the presence of the goddesses Hathor and Mut and nursing the child created by Khnum.

The early years of Amenhotep III

Amenhotep III's reign falls essentially into two unequal parts. The first decade reflected a young and vigorous king, promoting the sportsman image laid down by his predecessors and with some minor military activity. In Year 5 there was an expedition to Nubia, recorded on rock inscriptions near Aswan and at Konosso in Nubia. Although couched in the usual laudatory manner, the event recorded seems to have been rather low key. An undated stele from Semna (now in the British Museum) also records a Nubian campaign, but whether it is the same one or a later one is uncertain. A rebellion at Ibhet is reported as having been heavily crushed by the viceroy of Nubia, "King's Son of Kush", Merymose. Although the king, 'mighty bull, strong in might, the fierce-eyed lion' is noted as having made great slaughter within the space of a single hour, he was probably not present; nevertheless, 150 Nubian men, 250 women, 175 children, 110 archers, and 55 servan a total of 740 - were said to have been captured, to which was added the 312 right hands of the slain.

Amenhotep III's reign falls essentially into two unequal parts. The first decade reflected a young and vigorous king, promoting the sportsman image laid down by his predecessors and with some minor military activity. In Year 5 there was an expedition to Nubia, recorded on rock inscriptions near Aswan and at Konosso in Nubia. Although couched in the usual laudatory manner, the event recorded seems to have been rather low key. An undated stele from Semna (now in the British Museum) also records a Nubian campaign, but whether it is the same one or a later one is uncertain. A rebellion at Ibhet is reported as having been heavily crushed by the viceroy of Nubia, "King's Son of Kush", Merymose. Although the king, 'mighty bull, strong in might, the fierce-eyed lion' is noted as having made great slaughter within the space of a single hour, he was probably not present; nevertheless, 150 Nubian men, 250 women, 175 children, 110 archers, and 55 servan a total of 740 - were said to have been captured, to which was added the 312 right hands of the slain.

The opulent years of Amenhotep III

The last 25 years of Amenhotep III's reign seem to have been a period of great building works and luxury at court and in the arts. The laudatory epithets that accompany the king's name are more grandiose metaphen than records of fact: he took the Horus name 'Great of Strength who Smites the Asiatics', when there is little evidence of such a campaign, similarly, 'Plunderer of Shinar' and 'Crusher of Naharin' seem singularly inappropriate, particularly the latter since one of his wives, Gilukhepa, was a princess of Naharin.

The last 25 years of Amenhotep III's reign seem to have been a period of great building works and luxury at court and in the arts. The laudatory epithets that accompany the king's name are more grandiose metaphen than records of fact: he took the Horus name 'Great of Strength who Smites the Asiatics', when there is little evidence of such a campaign, similarly, 'Plunderer of Shinar' and 'Crusher of Naharin' seem singularly inappropriate, particularly the latter since one of his wives, Gilukhepa, was a princess of Naharin.

The wealth of Egypt at this period came not from the spoils of conquest, as it had under Tuthmosis III, but from international trade and an abundant supply of gold (from mines in the Wadi Hammamat and from panning gold dust far south into the land of Kush). It was this great wealth and booming economy that led to such an outpouring of artistic talent in all aspects of the arts.

Since the houses or palaces of the living were regarded as ephemeral, we unfortunately have little evidence of the magnificence of a palace such as Amenhotep's Malkata palace. Fragments of the building, however, indicate that the walls were once plastered and painted with lively scenes from nature. Many of the temples he built have been destroyed too. At Karnak he embellished the already large temple to Amun and at Luxor he built a new one to the same god, of which the still standing colonnaded court is a masterpiece of elegance and design. Particular credit is owed to his master architect: Amenhotep son of Hapu.

On the west bank, his mortuary temple was destroyed in the next (19th) dynasty when it, like many of its predecessors, was used as a quarry. All that now remains of this temple are the two imposing statues of the king known as the Colossi of Memnon. (This is in fact a complete misnomer, arising from the classical recognition of the statues as the Ethiopian prince, Memnon, who fought at Troy.) Of the two, the southern statue is the best preserved. Standing beside the king's legs, dwarfed by his stature, are the two important women in his life: his mother Mutemwiya and his wife, Queen Tiy. A quarter of a mile behind the Colossi stands a great repaired stele that was once in the sanctuary and around are fragments of sculptures, the best of which, lying in a pit and found in recent years, is a crocodile-tailed sphinx.

Since the houses or palaces of the living were regarded as ephemeral, we unfortunately have little evidence of the magnificence of a palace such as Amenhotep's Malkata palace. Fragments of the building, however, indicate that the walls were once plastered and painted with lively scenes from nature. Many of the temples he built have been destroyed too. At Karnak he embellished the already large temple to Amun and at Luxor he built a new one to the same god, of which the still standing colonnaded court is a masterpiece of elegance and design. Particular credit is owed to his master architect: Amenhotep son of Hapu.

On the west bank, his mortuary temple was destroyed in the next (19th) dynasty when it, like many of its predecessors, was used as a quarry. All that now remains of this temple are the two imposing statues of the king known as the Colossi of Memnon. (This is in fact a complete misnomer, arising from the classical recognition of the statues as the Ethiopian prince, Memnon, who fought at Troy.) Of the two, the southern statue is the best preserved. Standing beside the king's legs, dwarfed by his stature, are the two important women in his life: his mother Mutemwiya and his wife, Queen Tiy. A quarter of a mile behind the Colossi stands a great repaired stele that was once in the sanctuary and around are fragments of sculptures, the best of which, lying in a pit and found in recent years, is a crocodile-tailed sphinx.

A peak of artistic achievement of Amenhotep III