You want to show respect and love to the great revolutionary pharaoh Akhenaten? You can get one of these posters to hang on your wall! They are very cheap and they are very beautiful. I believe the average poster size is 18" x 24" (inches). And the average price is $20 to $40 US Dollars. However, prices and sizes will vary, just take a look at these outstanding posters that could bring both your wall and Akhenaten to life!

Just in case you are wondering, the two gray posters with a sun disk, represent the relatively-new revolutionary religion that Akhenaten has created with his wife (Nefertiti, who is also there with him in three of these posters). Akhenaten and Nefertiti have changed the country's religious views into monotheist views. Their god Aten (the sun-disk god) was praised and a new city (called Akhetaten or Amarna) was just built for that cause, and then the capital was moving from Thebes to Akhetaten for a while.

Amenhotep IV - better known as Akhenaten, the new name he took early on in his reign - ushered in a revolutionary period in Egypt history. The Amarna Interlude, as it is often called, saw the removal of the seat of government to a short-lived new capital city, Akhetaten (modern el-Amarna,

a new book is going to be released in a few weeks, make sure to pre-order it)

, the introduction of a new art style, and the elevation of the cult of the sun disc, the Aten, to pre-eminent status in Egyptian religion. This last heresy in particular was to bring down on Akhenaten and his immediate successors the opprobrium of later kings.

The young prince was at least the second son of Amenhotep III by his chief wife, Tiy: an elder brother, prince Tuthmosis, had died prematurely (strangely, a whip bearing his name was found in

Tutankhamun's tomb). There is some controversy over whether or not the old king took his son into partnership on the throne in a co-regency - there are quite strong arguments both for and against. A point in favour of a co-regency is the appearance during the latter years of Amenhotep III's reign of artistic styles that are subsequently seen as part of the 'revolutionary

Amarna art introduced by Akhenaten; on the other hand, both traditional' and 'revolutionary' art styles could easily have coexisted during the early years of Akhenaten's reign. At any rate, if there had been a coregency, it would not have been for longer than the short period before the new king assumed his preferred name of Akhenaten ('Servant of the Aten') in Year 5.

The beginning of Akhenaten's reign marked no great discontinuity with that of his predecessors. Not only was he crowned at Karnak (temple of the

god Amun) but, like his father, he married a lady of non-royal blood, Nefertiti, the daughter of the vizier Ay. Ay seems to have been a brother of Queen Tiy and a son of Yuya and Tuya. Nefertiti's mother is not known; she may have died in c;hildbirth or shortly afterwards, since Nefertiti seems to have been brought up by another wife of Ay named Tey, who would then be her stepmother.

Akhenaten and the cult of the Aten

There can be httle doubt that the new king was far more of a thinker and philosopher than his forebears. Amenhotep III had recognized the growing power of the priesthood of Amun and had sought to curb it; his son was to take the matter a lot further by introducing a new monotheistic cult of sun-worship that was incarnate in the sun's disc, the Aten.

This was not in itself a new idea: as a relatively minor aspect of the sun

god Re-Harakhte, the Aten had been venerated in the Old Kingdom and a large scarab of Akhenaten's grandfather Tuthmosis IV (now in the British Museum) has a text that mentions the Aten. Rather Akhenaten's innovation was to worship the Aten in its own right Portrayed as a solar disc whose protective rays terminated in hands holding the ankh hieroglyph for life, the Aten was accessible only to Akhenaten, thereby obviating the need for an intermediate priesthood.

At first, the king built a

temple to his

god Aten immediately outside the east gate of the

temple of Amun at Karnak, but clearly the coexis tence of the two cults could not last. He therefore proscribed the cult of Amun, closed the

god's temples, took over the revenues and, to make a complete break, in Year 6 moved to a new capital in Middle Egypt, half way between Memphis and Thebes. It was a virgin site, not previously dedicated to any other

god or

goddess, and he named it Akhetaten - The Horizon of the Aten. Today the site is known as

el-Amarna.

In the tomb of Ay, the chief minister of Akhenaten (and later to become king after

Tutankhamun's death, p. 136), occurs the longest and best rendition of a composition known as the 'Hymn to the Aten', said to have been written by Akhenaten himself. Quite moving in itself as a piece of poetry, its similarity to, and possible source of the concept in, Psalm 104 has long been noted. It sums up the whole ethos of the Aten cult and especially the concept that only Akhenaten had access to the

god: 'Thou arisest fair in the horizon of Heaven, 0 Living Aten, Beginner of Life ... there is none who knows thee save thy son Akhenaten. Thou hast made him wise in thy plans and thy power.' No longer did the dead call upon Osiris to guide them through the afterworld, for only through their adherence to the king and his intercession on their behalf could they hope to live beyond the grave.

According to present evidence, however, it appears that it was only the upper echelons of society which embraced the new religion with any fervour (and perhaps that was only skin deep). Excavations at .'

Amarna have indicated that even here the old way of religion continued among the ordinary people. On a wider scale, throughout Egypt, the new cult does not seem to have had much effect at a common level except, of course, in dismantling the priesthood and closing the temples; but then the ordinary populace had had little to do with the religious establishment anyway, except on the high days and holidays when the

god's statue would be carried in procession from the sanctuary outside the great

temple walls.

The standard bureaucracy continued its endeavours to run the country while the king courted his

god. Cracks in the Egyptian empire may have begun to appear in the later years of the reign of Amenhotep III; at any rate they became more evident as Akhenaten increasingly left government and diplomats to their own devices. Civil and military authority came under two strong characters: Ay, who held the title 'Father of the

God' land was probably Akhenaten's father-in-IawL and the general Horemheb (also Ay's son-in-law since he married Ay's daughter Mutnodjme, sister of Nefertiti). Both men were to become pharaoh before the 18th Dynasty ended. This redoubtable pair of closely related high officials no doubt kept everything under control in a discreet manner while Akhenaten pursued his own philosophical and religious interests.

The new artistic style of Akhenaten

It is evident from the art of the

Amarna period that the court officially emulated the king's unusual physical characteristics. Thus individuals such as the young princesses are endowed with elongated skulls and excessive adiposity, while Bek - the Chief Sculptor and Master of Works - portrays himself in the likeness of his king with pendulous breasts and protruding stomach. On a stele now in Berlin Bek states that he was taught by His Majesty and that the court sculptors were instructed to represent what they saw. The result is a realism that breaks away from the rigid formality of earlier official depictions although naturalism is very evident in earlier, unofficial art.

The power behind Akhenaten's throne?

Although the famous bust of Nefertiti in Berlin shows her with an elongated neck, the queen is not subject to quite the same extreme as others in

Amarna art, by virtue of being elegantly female. Indeed there are several curious aspects of Nefertiti's representation. early years of Akhenaten's reign, for instance, Nefertiti was an unusually prominent figure in official art, dominating the scenes carved on blocks of the

temple to the Aten at Karnak. One such block shows her in the age-old warlike posture of pharaoh grasping captives by the hair and smiting them with a mace - hardly the epitome of the peaceful queen and mother of six daughters. Nefertiti evidently played a far more prominent part in her husband's rule than was the norm.

Tragedy seems to have struck the royal family in about Year 12 with the death in childbirth of Nefertiti's second daughter, Mekytaten, it is probably she who is shown in a relief in the royal tomb with her stricken parents beside her supine body, and a nurse standing nearby holding a baby. The father of the infant was possibly Akhenaten, since he is also known to have married two other daughters, Merytaren (not to be confused with Mekytaten) and Akhesenpaaten (later to

Tutankhamun's wife).

Nefertiti appears to have died soon after Year 12, although some suggest that she was disgraced because her name was replaced in several instances by that of her daughter Merytaten, who succeed her as 'Great Royal Wife'. The latter bore a daughter called Merytaten-tasherit (Merytaten the Younger), also possibly fathered by Akhentaten. Merytaten was to become the wife of Smenkhkare, Akhenatten's brief successor. Nefertiti was buried in the royal tomb at

Amarna, judging by the evidence of a fragment of an alabaster ushabti figure bearing her cartouch found there in the early 1930s.

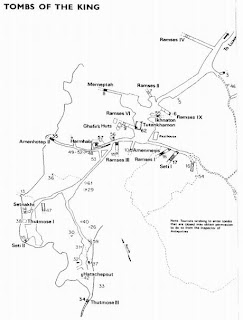

Akhetaten (or

el-Amarna as it is now known) is an important site because it was occupied neither before nor after its short life as capital under Akhenaten. It is ringed by a natural amphitheater of cliffs on both sides of the Nile and delineated by a series of 15 large stele carved in the rock around its perimeter. On the stele, reliefs show Akhenaten adoring his

god in the company of his wife and various of their six daughters, and give instructions that all should be buried within the city's sacred precincts. To this end a royal tomb was cut in a remote wadi situated mid-way between the tombs of the nobbles, now referred to the North and the South tombs.

None of the tombs was ever finished and probably few of them were actually occupied. If they were, loving relatives almost certainly rapidly removed the bodies immediately after the king's death, because of the backlash unleashed against him and his monuments.

The actual city was a linear development along part of the east bank, strentching back not very far into the desert where a number of small sun kiosks were located on the routes to the tombs. A broad thoroughfare, sometimes called the King's Road or Royal Avenue, linked the two ends of the city and was flanked by a series of official builders, including the royal palace (Great Palace), the new style open-air

temple to the Aten (the Great

Temple), and administrative offices. The Great Palace was probably a ceremonial center rather than a royal residence; the king and his family may have lived in the North Palace.The houses of the upper classes (mainly young nobles who had accompanied the king in his radical move) were arranged on an open plan, not crowded together as is usually found in the ancient Near East. Most were lavish buildings, with pools and gardens. The overall impression was that of a "garden city".

The whole essence of the court and life at

Amarna revolved around the king and his

god the Aten. Everywhere the royal family appeared they were shown to be under the protection of the Aten's rays. Reliefs in the tombs of the nobles at the site all focused on the king and through him the Aten.

Great scenes covered the walls and continued, unlike earlier and later tomb decoration, from wall to wall. The king, usually accompanied by Nefertiti and a number of their daughters, dominated the walls, normally in scenes showing them proceeding to the

temple of the Aten in chariots drawn by spirited and richly caparisoned horses. Small vignettes occur of men drawing water using shadufs (the ancient bucket and wieghted pole method that until recently was a common sight in Egypt, but is now fast disappearing); fat cattle are fed in their byres; blind musicians, their faces beautifully observed, sing the praises of Akhenaten and the Aten. Everything is alive and thriving under Akhenaten's patronage through the beneficence of the Aten.

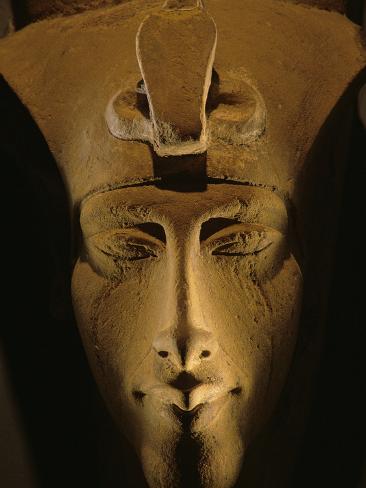

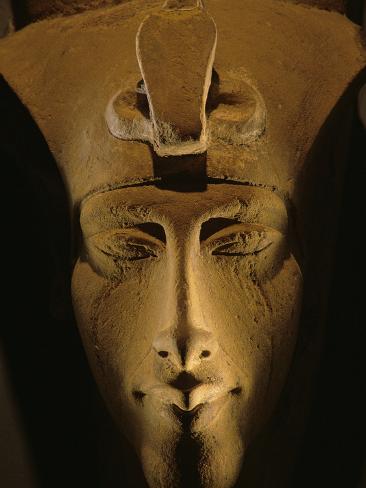

Akhenaten, Male or Female?

When the tomb of Akhenaten was rediscovered at

Amarna in the early 1880s, portraits of the royal couple were at first thought to represent two females, by virtue of Akhenaten's curious androgynous shape. One explanation for the king's unusual figure was that he suffered from a tumour of the pituitary gland, resulting in what is known as frohlich syndrome. Certain well-known effects of this disorder seem to be very evident in representations of Akhenaten; skull malformation; and lantern-like jaw; the head looking over-heavy on an elongated neck; excessive fat in areas that are more indicative of the female form, e.g. around the thighs, buttocks and breasts; and spindly legs. A side-effect of this condition, however, is infertility, and critics have pointed out that Akhenaten would have been unable to father the six daughters with whom he is so frequently shown on the other hand, he could have been struck by the illness at a later stage in his life.

Akhenaten's resting place

Akhenaten died c. 1334, probably in his 16th regnal year. Evidence found by Professor Geoffrey Martin during re-excavation of the royal tomb at

Amarna showed that blocking had been put in place in the burial chamber, suggesting that Akhenaten was buried there initially. Others do not believe that the tomb was used, however, in view of the heavily smashed fragments of his sarcophagus and canopic jars r recovered from it, and also the shattered examples of his ushabtis - found not only in the area of the tomb but also by Petrie in the city.

What is almost certain is that his body did not remain at

Amarna. A burnt mummy seen outside the royal tomb in the 1880s, and associated with Egyptian jewelry from the tomb (including a small gold finger ring with Nefertiti's cartouch), was probably Coptic, as was other Egyptian jewelry nearby. Akhenaten's adherents would not have left his body to be despoiled by his enemies once his death and the return to orthodoxy unleashed a backlash of destruction. They would have taken it to a place of safety - and where better to hide it than in the old royal burial ground at Thebes where enemies would never dream of seeking it?

Names, Family and Burial of Akhenaten

Akhenaten's Birth name: Amen-hotep (Amon is Pleased)

Also known as: Amenhotpe IV, Amenophis IV (Greek)

Adopted name (year 5) Akh-en-aten (Servant of the Aten)

Akhenaten's throne name: Nefer-kheperu-re (Beautiful are the Manifestations of Ra)

Akhenaten's father: Amenhotep III

Akhenaten's mother: Tiy

Akhenaten's wives: Nefertiti, Merytaten, Kiya, Mekytaten, Ankhesenpaaten

Akhenaten's daughters: Merytaten, Mekytaten, Ankhesenpaaten, Merytaten-tasherit and others

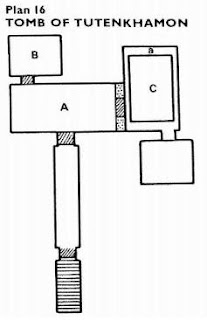

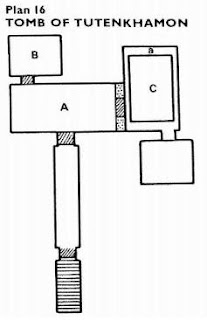

The disorder is undoubtedly indicative of hurry, as is the lack of decoration on the tomb walls. It is clear that the young king met a sudden death and was buried in haste. Murder? Suicide? Until 1969 the mummy revealed no secrets. But the results of an anthropological and skeletal examination of the Pharaoh's mummy, carried out by the Departments of Anatomy of Cairo and Liverpool Universities, are now at hand and it appears that death could have been caused by a blow on the head. Howard Carter had said that there was a 'scab' on the Pharaoh's head. Professor Harrison of Liverpool University claims that the unusual thinness of the outer skull of the mummy could have resulted from a hemorrhage beneath the membranes overlying the brain. The X-ray examination has ruled out the theory that Tutankhamun died of tuberculosis.

The disorder is undoubtedly indicative of hurry, as is the lack of decoration on the tomb walls. It is clear that the young king met a sudden death and was buried in haste. Murder? Suicide? Until 1969 the mummy revealed no secrets. But the results of an anthropological and skeletal examination of the Pharaoh's mummy, carried out by the Departments of Anatomy of Cairo and Liverpool Universities, are now at hand and it appears that death could have been caused by a blow on the head. Howard Carter had said that there was a 'scab' on the Pharaoh's head. Professor Harrison of Liverpool University claims that the unusual thinness of the outer skull of the mummy could have resulted from a hemorrhage beneath the membranes overlying the brain. The X-ray examination has ruled out the theory that Tutankhamun died of tuberculosis.

The disorder is undoubtedly indicative of hurry, as is the lack of decoration on the tomb walls. It is clear that the young king met a sudden death and was buried in haste. Murder? Suicide? Until 1969 the mummy revealed no secrets. But the results of an anthropological and skeletal examination of the Pharaoh's mummy, carried out by the Departments of Anatomy of Cairo and Liverpool Universities, are now at hand and it appears that death could have been caused by a blow on the head. Howard Carter had said that there was a 'scab' on the Pharaoh's head. Professor Harrison of Liverpool University claims that the unusual thinness of the outer skull of the mummy could have resulted from a hemorrhage beneath the membranes overlying the brain. The X-ray examination has ruled out the theory that Tutankhamun died of tuberculosis.

The disorder is undoubtedly indicative of hurry, as is the lack of decoration on the tomb walls. It is clear that the young king met a sudden death and was buried in haste. Murder? Suicide? Until 1969 the mummy revealed no secrets. But the results of an anthropological and skeletal examination of the Pharaoh's mummy, carried out by the Departments of Anatomy of Cairo and Liverpool Universities, are now at hand and it appears that death could have been caused by a blow on the head. Howard Carter had said that there was a 'scab' on the Pharaoh's head. Professor Harrison of Liverpool University claims that the unusual thinness of the outer skull of the mummy could have resulted from a hemorrhage beneath the membranes overlying the brain. The X-ray examination has ruled out the theory that Tutankhamun died of tuberculosis.