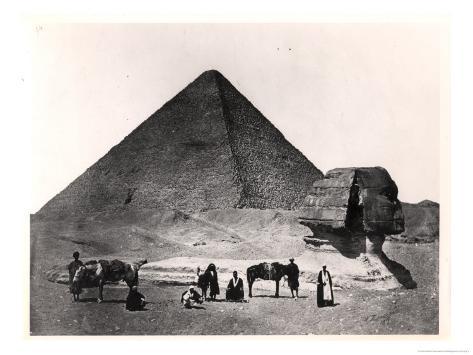

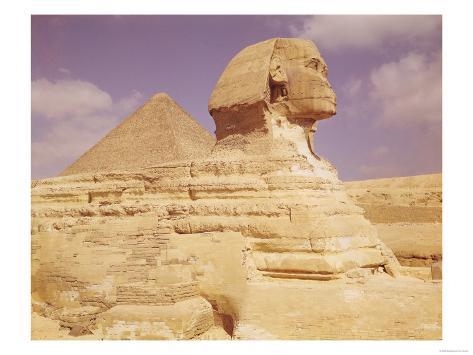

Egyptian civilization was the greatest civilization in the ancient world, and certainly the most long lived, lasting for more than 3000 years. In the popular mind the immediate images are those of the pyramids, the great Sphinx at Giza, the enormous

temples and the fabulous treasures that have been preserved in the dry sand of Egypt. But what of the people who were responsible for such splendors?The ancient Egyptian pharaohs were

god-kings on earth who became

gods in their own right at their death. They indeed held the power of life and death in their hands - their symbols of office, the crook and flail,

are indicative of this. They could command resources that many a modern-day state would be hard pressed to emulate. One has only to conjure with some statistics to realize this. For example, the Great Pyramid of

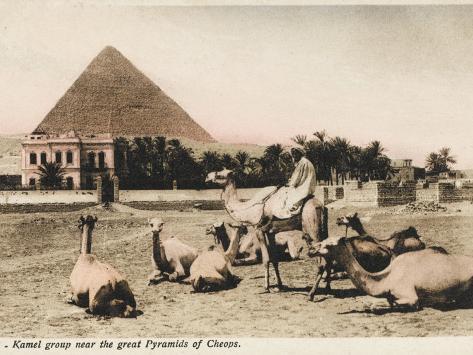

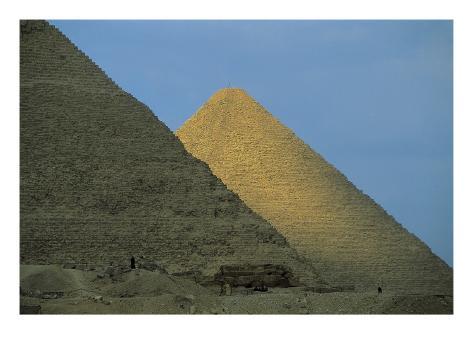

Khufu (Cheops) at Giza, originally 481 ft (146 m) high and covering 13.1 acres (5.3 hectares) was the tallest building in the world until the 19th century AD, yet it was constructed in the mid-3rd millennium BC, and we still do not know exactly how it was done. Its base area is so vast that it can accommodate the cathedrals of Florence, Milan, St Paul's and Westminster Abbey in London and St Peter's in Rome, and still have some space left over.

The vast treasures of precious metal and Egyptian jewelry that, miraculously, escaped the attentions of the tomb robbers are almost beyond comprehension.

Tutankhamun's solid gold inner coffin is a priceless work

of art; even at current scrap gold prices by weight it would be worth almost £1 million (£8.63 £892,262.27million) and his gold funerary mask £105,000 [). He was just a minor pharaoh of little consequence - the wealth of greater pharaohs such as Ramesses II, by comparison, is unimaginable.

The names of other great pharaohs resound down the centuries. The pyramid-builders numbered not merely

Khufu, but his famous predecessor Djoser - whose Step Pyramid dominates the royal necropolis at

Saqqara - and his successors Khafre (Chephren) and Menkaure (Mycerinus). Later monarchs included the warriors Tuthmosis III (Thutmose III), Amenhotep III, and Seti I, not to mention the infamous heretic-king

Akhenaten. Yet part of the fascination of taking a broad approach to Egyptian history is the emergence of lesser names and fresh themes. The importance of royal wives in a matrilineal society and the extent to which Egyptian queens could and did reign supreme in their own right Sobekneferu,

Hatshepsut, and Twosret to name but three - is only the most prominent among several newly emergent themes.

The known 170 or more pharaohs were all part of a line of royalty that stretched back to c. 3100 BC and forward to the last of the native pharaohs who died in 343 BC, to be succeeded by Persians and then a Greek line of Ptolemies until Cleopatra VII committed suicide in 30 BC. Following the 3rd-century BC High Priest of Heliopolis, Manetho whose list of Egyptian kings has largely survived in the writings of Christian clerics - we can divide much of this enormous span of time into 30 dynasties. Egyptologists today group these dynasties into longer eras, the three major pharaonic periods being the

Old, Middle and New Kingdoms, each of which ended in a period of decline given the designation

'Intermediate Period'.

In Chronicle of the Pharaohs, that emotive and incandescent 3000-year-old thread of kingship is

traced, setting the rulers in their context. Where possible, we gaze upon the face of pharaoh, either

via reliefs and statuary or, in some rare and thought provoking instances, on the actual face of the

mummy of the royal dead. Across the centuries the artist's conception reveals to us the

god-like com

placency of the Old Kingdom pharaohs, the care worn faces of the rulers of the Middle Kingdom, and

the powerful and confident features of the militant New Kingdom pharaohs. Such was their power in

Egypt, and at times throughout the ancient Near East, that Shelley's words, 'Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!', do indeed ring true as a reflection of their omnipotence.

Egypt and the Nile

Egypt is a land of extreme geographical contrasts, recognized by the ancient Egyptians in the names that they gave to the two diametrically opposed areas. The rich narrow agricultural strip alongside the Nile was called Kmt (Kemet or Kermet), 'The Black Land', while the inhospitable desert was Dsrt (Desert today), 'The Red Land'. Often, in Upper Egypt, the desert reaches the water's edge.

There was also a division between the north and the south, the line being drawn roughly in the area of modern Cairo. To the north was Lower Egypt where the Nile fanned out, with its several mouths, to form the Delta (the name coming from its inverted shape of the foutb letter, delta, of the Greek alphabet). To tbe south was Upper Egypt, stretching to Elephantine (modern Aswan). The two kingdoms, Upper and Lower Egypt, were united in c.3100 BC, but each had their own regalia. The low Red Crown (the deshret) represented Lower Egypt and its symbol was the papyrus plant. Upper Egypt was represented by the tall White Crown (the hedjet), its symbol being the flowering lotus. The combined Red and White crowns became the shmty. The two lands could also be embodied in The Two Ladies, respectively the cobra